Let's Talk About Forks and Cows

Part of Putting the “You” in CPU: a rabbit hole into how your computer runs programs.

The final question: how did we get here? Where do the first processes come from?

This article is almost done. We’re on the final stretch. About to hit a home run. Moving on to greener pastures. And various other terrible idioms that mean you are a single Length of Chapter 6 away from touching grass or whatever you do with your time when you aren’t reading 15,000 word articles about CPU architecture.

If execve starts a new program by replacing the current process, how do you start a new program separately, in a new process? This is a pretty important ability if you want to do multiple things on your computer; when you double-click an app to start it, the app opens separately while the program you were previously on continues running.

The answer is another system call: fork, the system call fundamental to all multiprocessing. fork is quite simple, actually — it clones the current process and its memory, leaving the saved instruction pointer exactly where it is, and then allows both processes to proceed as usual. Without intervention, the programs continue to run independently from each other and all computation is doubled.

The newly running process is referred to as the “child,” with the process originally calling fork the “parent.” Processes can call fork multiple times, thus having multiple children. Each child is numbered with a process ID (PID), starting with 1.

Cluelessly doubling the same code is pretty useless, so fork returns a different value on the parent vs the child. On the parent, it returns the PID of the new child process, while on the child it returns 0. This makes it possible to do different work on the new process so that forking is actually helpful.main.c

pid_t pid = fork();

// Code continues from this point as usual, but now across

// two "identical" processes.

//

// Identical... except for the PID returned from fork!

//

// This is the only indicator to either program that they

// are not one of a kind.

if (pid == 0) {

// We're in the child.

// Do some computation and feed results to the parent!

} else {

// We're in the parent.

// Probably continue whatever we were doing before.

}Process forking can be a bit hard to wrap your head around. From this point on I will assume you’ve figured it out; if you have not, check out this hideous-looking website for a pretty good explainer.

Anyways, Unix programs launch new programs by calling fork and then immediately running execve in the child process. This is called the fork-exec pattern. When you run a program, your computer executes code similar to the following:launcher.c

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// Immediately replace the child process with the new program.

execve(...);

}

// Since we got here, the process didn't get replaced. We're in the parent!

// Helpfully, we also now have the PID of the new child process in the PID

// variable, if we ever need to kill it.

// Parent program continues here...Mooooo!

You might’ve noticed that duplicating a process’s memory only to immediately discard all of it when loading a different program sounds a bit inefficient. Luckily, we have an MMU. Duplicating data in physical memory is the slow part, not duplicating page tables, so we simply don’t duplicate any RAM: we create a copy of the old process’s page table for the new process and keep the mapping pointing to the same underlying physical memory.

But the child process is supposed to be independent and isolated from the parent! It’s not okay for the child to write to the parent’s memory, or vice versa!

Introducing COW (copy on write) pages. With COW pages, both processes read from the same physical addresses as long as they don’t attempt to write to the memory. As soon as one of them tries to write to memory, that page is copied in RAM. COW pages allow both processes to have memory isolation without an upfront cost of cloning the entire memory space. This is why the fork-exec pattern is efficient; since none of the old process’s memory is written to before loading a new binary, no memory copying is necessary.

COW is implemented, like many fun things, with paging hacks and hardware interrupt handling. After fork clones the parent, it flags all of the pages of both processes as read-only. When a program writes to memory, the write fails because the memory is read-only. This triggers a segfault (the hardware interrupt kind) which is handled by the kernel. The kernel which duplicates the memory, updates the page to allow writing, and returns from the interrupt to reattempt the write.

A: Knock, knock!

B: Who’s there?

A: Interrupting cow.

B: Interrupting cow wh —

A: MOOOOO!

In the Beginning (Not Genesis 1:1)

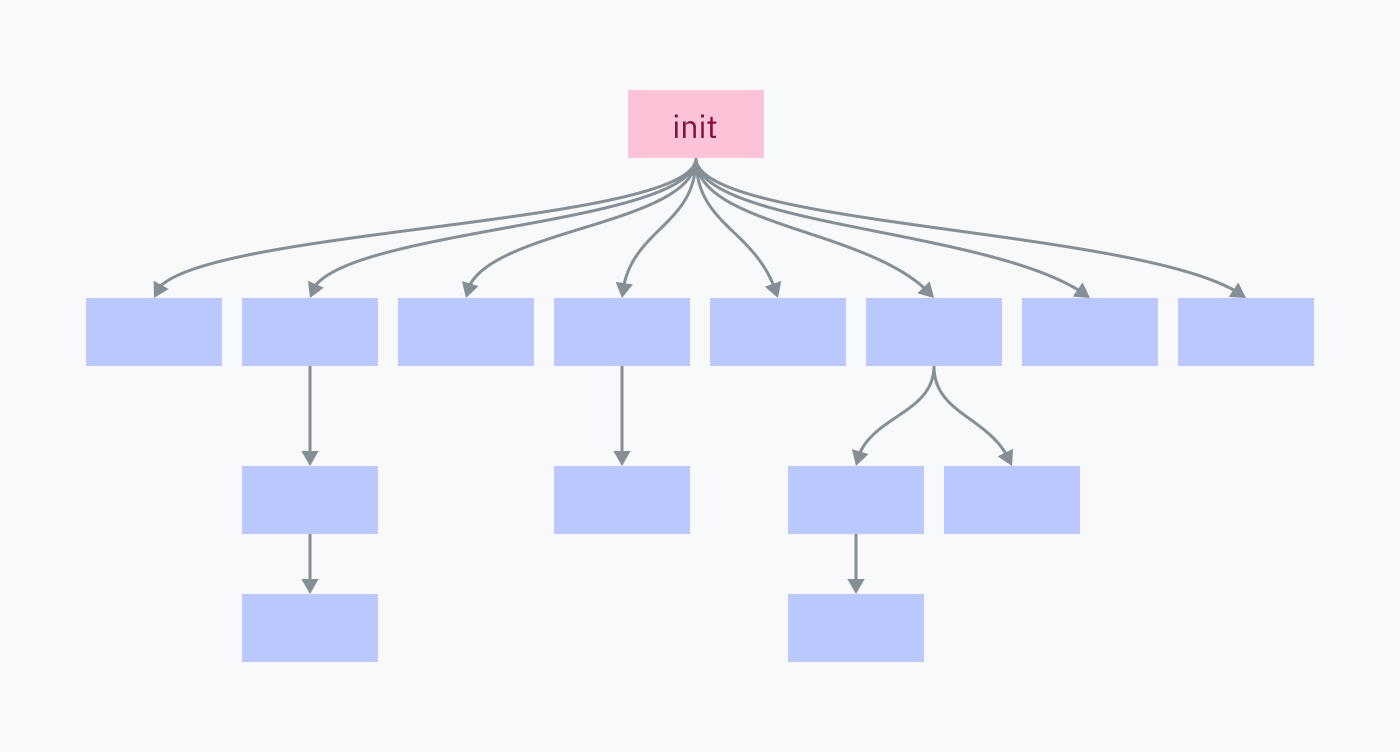

Every process on your computer was fork-execed by a parent program, except for one: the init process. The init process is set up manually, directly by the kernel. It is the first userland program to run and the last to be killed at shutdown.

Want to see a cool instant blackscreen? If you’re on macOS or Linux, save your work, open a terminal, and kill the init process (PID 1):Shell session

$ sudo kill 1Author’s note: knowledge about init processes, unfortunately, only applies to Unix-like systems like macOS and Linux. Most of what you learn from now on will not apply to understanding Windows, which has a very different kernel architecture.

Just like the section on

execve, I am explicitly addressing this — I could write another entire article on the NT kernel, but I am holding myself back from doing so. (For now.)

The init process is responsible for spawning all of the programs and services that make up your operating system. Many of those, in turn, spawn their own services and programs.

Killing the init process kills all of its children and all of their children, shutting down your OS environment.

Back to the Kernel

We had a lot of fun looking at Linux kernel code back in chapter 3, so we’re gonna do some more of that! This time we’ll start with a look at how the kernel starts the init process.

Your computer boots up in a sequence like the following:

- The motherboard is bundled with a tiny piece of software that searches your connected disks for a program called a bootloader. It picks a bootloader, loads its machine code into RAM, and executes it.Keep in mind that we are not yet in the world of a running OS. Until the OS kernel starts an init process, multiprocessing and syscalls don’t really exist. In the pre-init context, “executing” a program means directly jumping to its machine code in RAM without expectation of return.

- The bootloader is responsible for finding a kernel, loading it into RAM, and executing it. Some bootloaders, like GRUB, are configurable and/or let you select between multiple operating systems. BootX and Windows Boot Manager are the built-in bootloaders of macOS and Windows, respectively.

- The kernel is now running and begins a large routine of initialization tasks including setting up interrupt handlers, loading drivers, and creating the initial memory mapping. Finally, the kernel switches the privilege level to user mode and starts the init program.

- We’re finally in userland in an operating system! The init program begins running init scripts, starting services, and executing programs like the shell/UI.

Initializing Linux

On Linux, the bulk of step 3 (kernel initialization) occurs in the start_kernel function in init/main.c. This function is over 200 lines of calls to various other init functions, so I won’t include the whole thing in this article, but I do recommend scanning through it! At the end of start_kernel a function named arch_call_rest_init is called:start_kernel @ init/main.c

1087

1088 /* Do the rest non-__init'ed, we're now alive */

arch_call_rest_init();What does non-__init’ed mean?

The

start_kernelfunction is defined asasmlinkage __visible void __init __no_sanitize_address start_kernel(void). The weird keywords like__visible,__init, and__no_sanitize_addressare all C preprocessor macros used in the Linux kernel to add various code or behaviors to a function.In this case, __init is a macro that instructs the kernel to free the function and its data from memory as soon as the boot process is completed, simply to save space.

How does it work? Without getting too deep into the weeds, the Linux kernel is itself packaged as an ELF file. The

__initmacro expands to__section(".init.text"), which is a compiler directive to place the code in a section called.init.textinstead of the usual.textsection. Other macros allow data and constants to be placed in special init sections as well, such as__initdatathat expands to__section(".init.data").

arch_call_rest_init is nothing but a wrapper function:init/main.c

832

833

834

835void __init __weak arch_call_rest_init(void)

{

rest_init();

}The comment said “do the rest non-__init’ed” because rest_init is not defined with the __init macro. This means it is not freed when cleaning up init memory:init/main.c

689

690noinline void __ref rest_init(void)

{rest_init now creates a thread for the init process:rest_init @ init/main.c

695

696

697

698

699

700 /*

* We need to spawn init first so that it obtains pid 1, however

* the init task will end up wanting to create kthreads, which, if

* we schedule it before we create kthreadd, will OOPS.

*/

pid = user_mode_thread(kernel_init, NULL, CLONE_FS);The kernel_init parameter passed to user_mode_thread is a function that finishes some initialization tasks and then searches for a valid init program to execute it. This procedure starts with some basic setup tasks; I will skip through these for the most part, except for where free_initmem is called. This is where the kernel frees our .init sections!kernel_init @ init/main.c

1471 free_initmem();Now the kernel can find a suitable init program to run:kernel_init @ init/main.c

1495

1496

1497

1498

1499

1500

1501

1502

1503

1504

1505

1506

1507

1508

1509

1510

1511

1512

1513

1514

1515

1516

1517

1518

1519

1520

1521

1522

1523

1524

1525 /*

* We try each of these until one succeeds.

*

* The Bourne shell can be used instead of init if we are

* trying to recover a really broken machine.

*/

if (execute_command) {

ret = run_init_process(execute_command);

if (!ret)

return 0;

panic("Requested init %s failed (error %d).",

execute_command, ret);

}

if (CONFIG_DEFAULT_INIT[0] != '\0') {

ret = run_init_process(CONFIG_DEFAULT_INIT);

if (ret)

pr_err("Default init %s failed (error %d)\n",

CONFIG_DEFAULT_INIT, ret);

else

return 0;

}

if (!try_to_run_init_process("/sbin/init") ||

!try_to_run_init_process("/etc/init") ||

!try_to_run_init_process("/bin/init") ||

!try_to_run_init_process("/bin/sh"))

return 0;

panic("No working init found. Try passing init= option to kernel. "

"See Linux Documentation/admin-guide/init.rst for guidance.");On Linux, the init program is almost always located at or symbolic-linked to /sbin/init. Common inits include systemd (which has an abnormally good website), OpenRC, and runit. kernel_init will default to /bin/sh if it can’t find anything else — and if it can’t find /bin/sh, something is TERRIBLY wrong.

MacOS has an init program, too! It’s called launchd and is located at /sbin/launchd. Try running that in a terminal to get yelled for not being a kernel.

From this point on, we’re at step 4 in the boot process: the init process is running in userland and begins launching various programs using the fork-exec pattern.

Fork Memory Mapping

I was curious how the Linux kernel remaps the bottom half of memory when forking processes, so I poked around a bit. kernel/fork.c seems to contain most of the code for forking processes. The start of that file helpfully pointed me to the right place to look:kernel/fork.c

8

9

10

11

12

13/*

* 'fork.c' contains the help-routines for the 'fork' system call

* (see also entry.S and others).

* Fork is rather simple, once you get the hang of it, but the memory

* management can be a bitch. See 'mm/memory.c': 'copy_page_range()'

*/It looks like this copy_page_range function takes some information about a memory mapping and copies the page tables. Quickly skimming through the functions it calls, this is also where pages are set to be read-only to make them COW pages. It checks whether it should do this by calling a function called is_cow_mapping.

is_cow_mapping is defined back in include/linux/mm.h, and returns true if the memory mapping has flags that indicate the memory is writeable and isn’t shared between processes. Shared memory doesn’t need to be COWed because it is designed to be shared. Admire the slightly incomprehensible bitmasking:include/linux/mm.h

1541

1542

1543

1544static inline bool is_cow_mapping(vm_flags_t flags)

{

return (flags & (VM_SHARED | VM_MAYWRITE)) == VM_MAYWRITE;

}Back in kernel/fork.c, doing a simple Command-F for copy_page_range yields one call from the dup_mmap function… which is in turn called by dup_mm… which is called by copy_mm… which is finally called by the massive copy_process function! copy_process is the core of the fork function, and, in a way, the centerpoint of how Unix systems execute programs — always copying and editing a template created for the first process at startup.https://www.youtube.com/embed/FavUpD_IjVY

In Summary…

So… how do programs run?

On the lowest level: processors are dumb. They have a pointer into memory and execute instructions in a row, unless they reach an instruction that tells them to jump somewhere else.

Besides jump instructions, hardware and software interrupts can also break the sequence of execution by jumping to a preset location that can then choose where to jump to. Processor cores can’t run multiple programs at once, but this can be simulated by using a timer to repeatedly trigger interrupts and allowing kernel code to switch between different code pointers.

Programs are tricked into believing they’re running as a coherent, isolated unit. Direct access to system resources is prevented in user mode, memory space is isolated using paging, and system calls are designed to allow generic I/O access without too much knowledge about the true execution context. System calls are instructions that ask the CPU to run some kernel code, the location of which is configured by the kernel at startup.

But… how do programs run?

After the computer starts up, the kernel launches the init process. This is the first program running at the higher level of abstraction where its machine code doesn’t have to worry about many specific system details. The init program launches the programs that render your computer’s graphical environment and are responsible for launching other software.

To launch a program, it clones itself with the fork syscall. This cloning is efficient because all of the memory pages are COW and the memory doesn’t need to be copied within physical RAM. On Linux, this is the copy_process function in action.

Both processes check if they’re the forked process. If they are, they use an exec syscall to ask the kernel to replace the current process with a new program.

The new program is probably an ELF file, which the kernel parses to find information on how to load the program and where to place its code and data within the new virtual memory mapping. The kernel might also prepare an ELF interpreter if the program is dynamically linked.

The kernel can then load the program’s virtual memory mapping and return to userland with the program running, which really means setting the CPU’s instruction pointer to the start of the new program’s code in virtual memory.

Epilogue

Part of Putting the “You” in CPU: a rabbit hole into how your computer runs programs.

Congratulations! We have now firmly placed the “you” in CPU. I hope you had fun.

I will send you off by emphasizing once more that all the knowledge you just gained is real and active. The next time you think about how your computer is running multiple apps, I hope you envision timer chips and hardware interrupts. When you write a program in some fancy programming language and get a linker error, I hope you think about what that linker is trying to do.

If you have any questions (or corrections) about anything contained in this article, you should email me at lexi@hackclub.com or submit an issue or PR on GitHub.

… but wait, there’s more!

Bonus: Translating C Concepts

If you’ve done some low-level programming yourself, you probably know what the stack and the heap are and you’ve probably used malloc. You might not have thought a lot about how they’re implemented!

First of all, a thread’s stack is a fixed amount of memory that’s mapped to somewhere high up in virtual memory. On most (although not all) architectures, the stack pointer starts at the top of the stack memory and moves downward as it increments. Physical memory is not allocated up-front for the entire mapped stack space; instead, demand paging is used to lazily allocate memory as frames of the stack are reached.

It might be surprising to hear that heap allocation functions like malloc are not system calls. Instead, heap memory management is provided by the libc implementation! malloc, free, et al. are complex procedures, and the libc keeps track of memory mapping details itself. Under the hood, the userland heap allocator uses syscalls including mmap (which can map more than just files) and sbrk.

Bonus: Tidbits

I couldn’t find anywhere coherent to put these, but found them amusing, so here you go.

Most Linux users probably have a sufficiently interesting life that they spend little time imagining how page tables are represented in the kernel.

An alternate visualization of hardware interrupts:

A note that some system calls use a technique called vDSOs instead of jumping into kernel space. I didn’t have time to talk about this, but it’s quite interesting and I recommend reading into it.

And finally, addressing the Unix allegations: I do feel bad that a lot of the execution-specific stuff is very Unix-specific. If you’re a macOS or Linux user this is fine, but it won’t bring you too much closer to how Windows executes programs or handles system calls, although the CPU architecture stuff is all the same. In the future I would love to write an article that covers the Windows world.

Acknowledgements

I talked to GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 a decent amount while writing this article. While they lied to me a lot and most of the information was useless, they were sometimes very helpful for working through problems. LLM assistance can be net positive if you’re aware of their limitations and are extremely skeptical of everything they say. That said, they’re terrible at writing. Don’t let them write for you.

More importantly, thank you to all the humans who proofread me, encouraged me, and helped me brainstorm — especially Ani, B, Ben, Caleb, Kara, polypixeldev, Pradyun, Spencer, Nicky (who drew the wonderful elf in chapter 4), and my lovely parents.

If you are a teenager and you like computers and you are not already in the Hack Club Slack, you should join right now. I would not have written this article if I didn’t have a community of awesome people to share my thoughts and progress with. If you are not a teenager, you should give us money so we can keep doing cool things.

All of the mediocre art in this article was drawn in Figma. I used Obsidian for editing, and sometimes Vale for linting. The Markdown source for this article is available on GitHub and open to future nitpicks, and all art is published on a Figma community page.

Discover more from Shaynly

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.